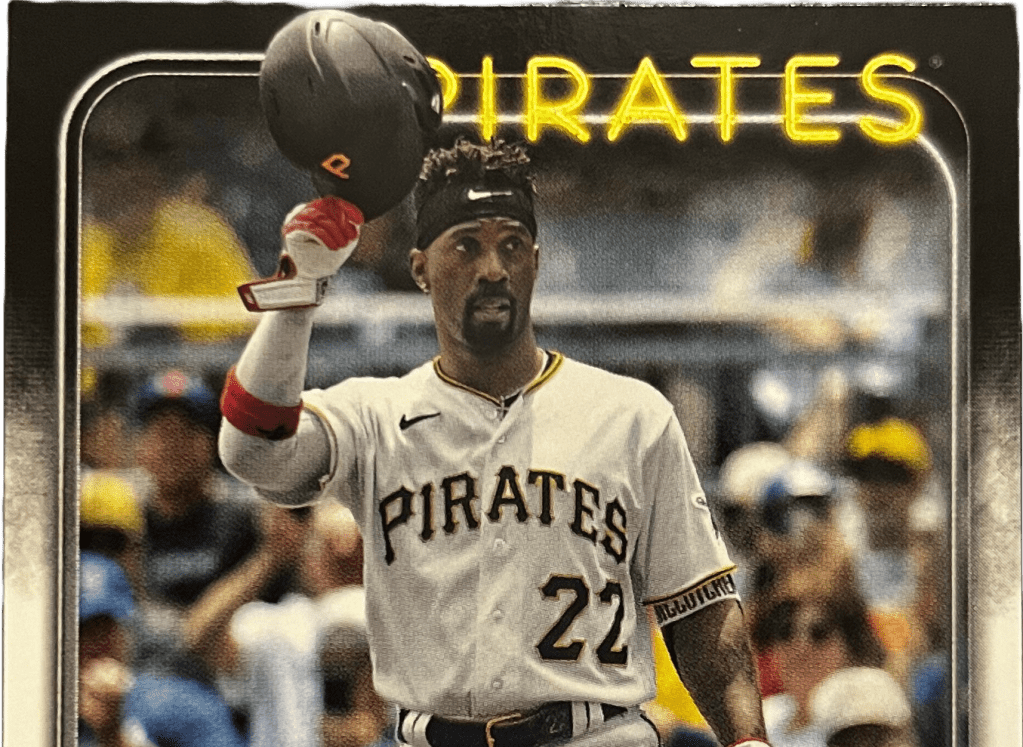

What’s the worst season of Pirates baseball you’ve ever watched?

There have been some really bad seasons in recent history for the Bucs. The 2010 Pirates went 57-105. The 2020 team was on pace for over 100 losses on the year, going 19-41 in the Covid year. The Pirates successfully played back to back 100-loss seasons in 2021 and 2022.

In franchise history, the Pirates have lost 100+ games on ten different occasions. And while four of those seasons have come in this century, while the others have been scattered around the seemingly endless decades of baseball in the Steel City.

However, one season stands out amongst the rest. One season has to be the worst, and because I’m a pessimist, let’s talk about that season today. Allow me to take you all the way back to the black and white world of 1890, where amidst all the smoke and smog of the city, we will find a truly awful baseball team.

We’re going so far back in history that the Pirates weren’t even known as the Pirates back then. In fact, they didn’t even play in Pittsburgh at the time.

Today, we know it as Pittsburgh’s North Side, but from 1788 to 1907, the North Side existed as its own separate city: Allegheny City. This now defunct city served the original home of the baseball club we know and love today in the late 1880s and early 1890s.

They did not have an official team name, being known only as Allegheny City in the standings. However, they were commonly informally known as the Alleghenys at the time.

The 1890 season was actually the team’s last under the Allegheny City banner; the team would officially adopt the Pittsburgh name starting in 1891.

But man did the Alleghenys make it easier for the Allegheny City residents to watch their team move across the river. The team went 23-113-2 that season, the most losses in franchise history. Their winning percentage of .169 was the only season in team history where the overall winning percentage started with a 1.

Now, it’s vital to note that baseball was so much less organized than it is today. Both the American Association (which was essentially a precursor to the American League) and National League were on shaky ground, and disagreements with players were frequent.

Such was the case in 1890, when a majority of Allegheny City’s players jumped ship from the team to join the Pittsburgh Burghers of the newly minted Players’ League.

The Players’ League was formed out of a dispute with the National League and the American Association over pay. Both leagues had instituted a salary cap of $2,000 per player in 1885, which is equivalent to a little under $59,000 in 2024. The players didn’t like it, and pushed for it to be repealed.

Team owners had agreed to remove the salary cap in 1887, but failed to follow through, only leading to more anger from a variety of players. Finally, the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players, a union of most of the game’s best players in the current leagues at the time, formed a new league in November of 1889, set to play their first season the year later.

Help support the Fifth Avenue Sports publication!

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount:

Or enter a custom amount:

Contributions help ensure that Fifth Avenue Sports can continue to survive and grow in the sports media realm. I cannot possibly thank you enough for your support and generosity in supporting my work!

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonateDonatePittsburgh was named as one of eight cities to be getting teams in the new league.

Many teams in both the NL and AA suffered departures to the Players’ League, but Allegheny City was hit extremely hard by the new team moving in down the street. Ex-Alleghenys who left for the Burghers included Pud Galvin, Ned Hanlon, and Jake Beckley, all of whom are now baseball Hall of Famers.

While the grass was certainly greener with Pittsburgh as opposed to Allegheny City that season, the Burghers didn’t necessarily have a great season either. They finished 60-68, which was good for sixth place in the eight-team Players’ League. They finished 20.5 games back of the league champion Boston Reds.

They struggled overall to generate offense, finishing tied for last in team batting average at .260.

But despite the underwhelming season for the Burghers in the Players’ League, it was nothing compared to the disaster the Alleghenys had become.

Forced to pick up the pieces after losing essentially every star-level player they had, the Alleghenys did what they could to cobble together whatever kind of roster they could, while their old friends puttered around across the river.

Not only was their record laughably bad in the National League, it also helped them make the wrong side of baseball history on more than one occasion. Their 113 losses set a new major league record, which would stand until the Cleveland Spiders lost 134 games in 1899, a record that still stands today.

And just as a side note: if you thought this season was bad for the Alleghenys, you have to read up more on the 1899 Cleveland Spiders. You ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

The Alleghenys’ also suffered poor attendance at their games (and who could blame fans for not wanting to watch this trainwreck?), meaning a lot of their games ended up being scheduled to be on the road. In all, the Alleghenys played 97 of their 138 games away from the city, and did not play a single home game in the month of May.

Allegheny City posted a road record of 9-88, a record that would also stand until the Spiders broke it in 1899.

Meanwhile, back home at the lovely named Recreation Park, the Alleghenys went 14–25, which is still bad, but a hell of a lot more respectable than their road performances.

The season actually started out rather well for the Alleghenys. They opened the season at home, winning their season debut on April 19th against Cleveland by a final score of 3-2.

Allegheny City actually took three of four from the Spiders to open the season, including scoring a season-high 20 runs in 20-12 win over the Spiders.

After that, they split a mini two-game series vs the Cincinnati Reds, making for a 4-2 home stand to open the year. They were supposed to host the Chicago Colts as well, but that ended up being the first of many series that was moved out of Allegheny City and into the opposing ballpark.

An April 30th loss vs the Colts dropped the team to 4-4 on the year. This would be the last day the Alleghenys were at or above .500. Things were only going downhill from here.

The team only won four games in the month of May, and as mentioned before, not a single game was played at home. They suffered a ten game losing streak towards the end of the month that really put any kind of winning baseball out of reach.

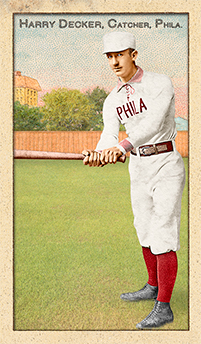

June was a notable month for more than one reason for the Alleghenys. First off, team acquired catcher Harry Decker from Philadelphia for cash on June 4th. Decker would go on to lead the team in batting average (among qualified players) and home runs.

June also meant that no one named Henry was allowed to be on the team anymore; on June 2nd, the team released pitcher Henry Jones and infielder Henry Youngman, who was in fact only 24 at the time.

The releasing of Jones was not ideal if Allegheny City’s intentions were to win games. Jones’ 3.48 ERA through 31.0 innings was amongst the lowest on the team at season’s end.

Also happening in June, however: the Alleghenys were finally allowed to play a series at home to start June, but in their first action back in Recreation Park, they were swept by Chicago.

In their next series at home, they successfully nabbed two of three from the Spiders, so at least the few hundred spectators in attendance those days had some good memories.

Their final home stand in June saw them swept for a second time, dropping four straight against Boston. However, to their credit, the Alleghenys did take three of four from the New York Giants at home in a series that started on the final day of June.

Thanks to that, July started with three straight wins for Allegheny City, but those good vibes were ended immediately after the Giants left down. The Alleghenys lost 13 straight games after that series, and while that seemed bad enough, August was even worse.

Not even the signing of a man by the name of Peek-A-Boo Veach could help salvage the happiness. Three days after being released by the Cleveland Spiders, the Alleghenys signed Veach and brought him to the team.

Veach would appear in just eight games for the club, batting .300 with 2 home runs and 5 RBI before being released by Allegheny City on August 3rd, because good baseball is not what this team is about!

From August 12th to September 2nd, the Alleghenys did not see a win, losing 21 straight games to plummet them to a 19-93 record by the time the streak ended. That streak, by the way, of course ended with a matchup against the Cleveland Spiders, who routinely found a way to bring little pockets of sunshine to a smog and dark Alleghenys season.

Despite the Spiders still massively winning the season series, the Alleghenys went 6-12-1 against Cleveland, which was more wins (and a higher winning percentage) they had than against any other team.

September, as one would expect, didn’t get any better. Several smaller losing streaks continued to rack up an embarrassing loss total. Their final win of the year came on September 30th, a surprising 10-1 win over Philadelphia.

When the season was finished, the Alleghenys were a whopping 66.5 games back, and absolutely buried in last place in the National League.

Among qualifying players, catcher Harry Decker led the way in both batting average (.274) and home runs (5). Five players had a higher batting average than Decker, but none of them played in more than ten games.

Third baseman George Miller led the team in RBI, with 66. Miller also drew a team leading 68 walks while striking out just 11 times all season.

Speedy outfielder Billy Sunday led the team in stolen bases, with 56. He maintained the team lead despite being traded to Philly on August 22nd for two players and $1,100 in cold hard cash. Neither player acquired in the deal made much of an impact, or stuck with the team past 1890.

Over in the pitching department, the aptly named Phenomenal Smith led the team in ERA, with a 3.07 ERA over 31.0 innings. He was one of only two pitchers on the entire staff that season to have a strikeout to walk ratio of over 1.00, at 1.15.

The other was Bill Sowders, who led the way among starting pitchers with a 4.42 ERA over 106 innings pitched. He had a strikeout to walk ratio of 1.25 on the year.

The only pitcher with a winning record was the aforementioned Henry Jones, who was released mid-season. So among pitchers who ended the year in Allegheny City, the closest (ranked by winning percentage) was Billy Gumbert, who went 4-6 while posting a 5.22 ERA in 79.1 innings pitched.

The Alleghenys really adopted a pitching by committee type approach to the 1890 season; they led the NL in most pitchers used, with 22. The second highest was 12.

Allegheny City scored a total of 597 runs that season. They allowed 1,235. That, my friends, is a differential of 638 runs.

A full look at the 1890 Allegheny City roster can be found here.

The Players’ League collapsed after their one and only season in 1890. Management of the new league lacked funding to keep it going, and many in charge lost faith that the league could really take off and survive long term. As such, a lot of the Players’ League teams merged with their National League and American Association counterparts.

For Allegheny City and the Pittsburgh Burghers, this meant a merger that saw the Alleghenys reunite with many of their star players, such as Ned Hanlon, Jake Beckley, Harry Staley, and others.

It also saw the team move across the river from Allegheny City and adopt the Pittsburgh banner. Though not officially taking on a new name, they were essentially given one after the Lou Bierbauer incident.

The Players’ League merger back into the NL and AA was not entirely seamless. Lou Bierbauer was one of many players who had jumped ship to the PL, leaving the Philadelphia Athletics of the NL to go play for the Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders.

The PL had really taken its toll on some existing teams in the NL and AA, and his old team in Philadelphia was no exception. The Athletics completely collapsed in 1890; despite a stellar first half to their season, things were unraveling behind the scenes.

Their owners could not afford to keep paying the majority of their players; they sold off stars and eventually sold off anybody who was on the roster, and several players also reportedly deserted the team. The Athletics finished the 1890 season with a cheaply constructed pickup team; they lost their final 22 games of the season.

That version of the Athletics was removed from the AA after 1890, and was replaced by the PL version by the same name. Many of the old Athletics players signed with the new Philadelphia team, but one notable name was absent: Lou Bierbauer.

Bierbauer never officially signed with the new Athletics, and the team neglected to put him on the reserve list, perhaps taking for granted the fact he would return on his own. Noticing this, Pittsburgh moved to add him instead.

Legend has it that Ned Hanlon, who in addition to being a player was also serving as the manager in Pittsburgh, traveled to Bierbauer’s native Erie, PA dead of winter to get the deal done.

Realizing their mistake, the Athletics objected and called Pittsburgh’s actions “piratical.” They claimed that Bierbauer should have been returned to Philadelphia after leaving the failed PL, but Pittsburgh argued that since the Athletics did not have Bierbauer on a reserve list, he was a “free agent.”

Arbitrators eventually sided with Pittsburgh, and the team was called “pirates” for their actions regarding Bierbauer. The team adopted that nickname starting in 1891, but they was not officially recognized in league standings as the “Pittsburgh Pirates” until 1895.

In all, the team left Allegheny City after nine years, putting up a total record of 441-617-16. Their reported season attendance (among games that were counted) was 16,064.

(Featured photo is a drawing of Recreation Park, which first appeared in The Pittsburgh Press on October 11th, 1894)

Leave a comment