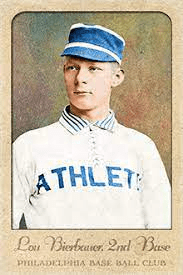

In discussing how the Pittsburgh Pirates got their name, the Lou Bierbauer incident is often chalked up as the reason why.

In 1890, a rebellion league known as the Players’ League formed, and consisted of nearly all members of the and nearly every star player from The Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players, a very early version of the MLBPA. Players from both the National League and American Association (a precursor to the American League, but with no direct link) had jumped from their current leagues to the new one.

Though the PL, who boasted the most talent out of any of the three leagues at the time, was very successful at stealing away the NL and AA’s audience, they lacked solid financial footing and ultimately lasted only one year. The PL’s collapse resulted in most players crawling back to their former NL and AA teams.

Lou Bierbauer left the AA’s Philadelphia Athletics to play for Brooklyn of the PL in 1890. However, a glaring clerical error meant that the Athletics had inadvertently left Bierbauer off their reserve list, making him a “free agent.”

The Alleghenys (the Pirates’ name prior to 1890) noticed this and moved to sign the second baseman to their club instead. When Philadelphia caught wind of this, they objected, and officials from the AA called the Alleghenys’ act “piratical.”

Bierbauer was eventually allowed to sign in the Smoky City after it was ruled that Philadelphia had no claim to him, since they had neglected to put him on their reserve list.

That’s the story that most people know as to why Pittsburgh’s baseball team is known as the Pirates. But the Bierbauer event is not the only act of “piracy” that the club has undergone in its history. In fact, it’s not even the only instance of it in 1890.

But to find out that story, we have to meet a man by the name of Mark Baldwin.

Baldwin’s time as a big league baseball player is rife with conflicts and controversy.

A Pittsburgh native, Baldwin bounced around the country, appearing for any team that he could get involved in. But his breakout season came in Minnesota in 1886, when he helped lead the Duluth Jayhawks to the Northwestern League pennant. He was credited with winning 27 of the team’s 83 games that year, and also filled in at shortstop when he was not pitching for the Jayhawks.

That season put him on the map, and on October 20th, 1886, Baldwin signed with the Chicago White Stockings of the National League. At the time he was signed, Chicago was facing off with the American Association’s St. Louis Browns in the pre-modern version of the World Series.

Two days later, on October 22nd, with the series tied 2-2 and Chicago dealing with a string of injured and taxed pitchers, player-manager Cap Anson tried to put Baldwin in the lineup at pitcher.

The crowd of roughly 16,000 at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis “bowed their objection” and Browns owner Chris von der Ahe immediately objected, on the grounds that Baldwin had not appeared on Chicago’s roster during the 1886 season.

Ironically, Chicago’s owner, Albert G. Spalding, had previously objected to St. Louis’ attempt to use Toad Ramsey, who spent the 1886 season with the Louisville Colonels, for the series. Umpires eventually sided with St. Louis, forcing Chicago to scrape together innings from their position players.

The Browns won easily, putting up a 10-3 score before the game was called because it got too dark outside (you know, in the same way that you had to stop the backyard game with your friends because none of you could see the ball anymore).

St. Louis would take the series the next day, but it was far from the only conflict that Baldwin and von der Ahe would have.

Baldwin got his official start in the NL the following year. He joined the White Stockings for spring training in Hot Springs, Arkansas, but an incident at the team’s hotel nearly killed him before he made his debut.

On March 17th, a hotel employee smelled gas coming from the room of Baldwin and teammate Tom Daly. Concerned, the employee broke down the door and found both men unconscious. They immediately called for a doctor and both Baldwin and Daly were successfully revived. It was later revealed that one of them had accidentally blown out the flame in the gaslight.

Baldwin pitched to an 18-17 record for Chicago in 1887, with 164 strikeouts and 122 walks in 334 innings pitched.

When on the mound, Baldwin showed some incredible power in his arm and an impressive arsenal, but he struggled with control. His 41 wild pitches led the NL. Despite the wildness, the White Stockings were confident in his progression as a big league pitcher, which made them feel more comfortable selling John Clarkson to Boston for $10,000.

Clarkson had accounted for 38 wins and 523 innings for the third-placed White Stockings in 1887, and his sale resulted in local media claiming that Anson had to be the only one that still believed the White Stockings could win a pennant.

However, Chicago almost proved the critics wrong, putting up a 77-58-1 season in 1888, finishing second place in the NL. While they had a very good year contrary to expectations, they finished nine games back of New York for the year.

Anson did his part from first base. He led the league with a .344 batting average and 84 RBI. Baldwin, meanwhile, posted a 13-15 record with a. An injury to his leg kept him out of the lineup for a month and a half, but Baldwin tried to help bring in reinforcements in his absence by attempting to convince Anson to sign his friend John Tener, who pitched on local sandlots until a pro team came calling.

On a trip to Pittsburgh in August, Anson gave him a contract after seeing him pitch; Tener would provide the White Stockings with 102 innings at a 2.74 ERA that season.

After the 1888 season, Baldwin was invited to accompany Chicago owner Spalding and many of his teammates on a barnstorming world tour, where Spalding would organize games between his White Stockings and the “All Americans” which was comprised of players from various other teams.

Spalding wanted to introduce the game to the rest of the globe (and plant seeds in other markets to further his own business endeavors) and organized games to be played in Australia, Egypt, Italy, France, England, Ireland, as well as locations within the United States.

The Spalding World Tour, as it came to be known, is one of the more fascinating sports tours in history, and has since been the topic of many books and other writings.

Let’s just say that things on the tour got…hmm, a little rowdy.

The tour was filled with alcohol and chaos, and one of the more infamous stories from that tour is Baldwin antagonized a monkey onboard a cruise ship. It then leaped for Baldwin, scratching and biting at his leg. Anson had to put Baldwin on bedrest, and Baldwin reportedly threatened to shoot the monkey, though sources claimed he did not follow through on that.

Baldwin also reportedly ran out of money on the trip, having to borrow over $800 from Spalding during the tour.

Like an exhausted chaperone on a class field trip, Spalding grew tired of the antics of Baldwin and friends over the course of the tour, and on Opening Day of the 1888 season, Spalding released Baldwin, as well as Daly, Marty Sullivan, and Bob Pettit.

Similarly, Anson said that he would rather “have a team of gentlemen and would rather take eighth place with it than first with a gang of roughs.”

Baldwin, however, would hint that a disagreement in salary was the reason he was released, and later on, Anson claimed his wildness on the mound was the cause.

“Mark Baldwin would be a great pitcher if he learned how to control the ball,” he said. “That is his weak point, and that was one of my reasons for letting him go

Baldwin was miffed at the timing of his release, and equally surprised at his lack of ability to find work within the NL. With the season already underway, he was forced to jump to the AA, where he signed with the Columbus Solons on May 3rd.

Baldwin would appear in a career high 513.2 innings for Columbus. There, he was able to hone in on strikeouts, recording a league leading 368 Ks, more than 150 more than the second place arm.

True to form, however, he also led the league with a whopping 83 wild pitches, more than double the next closest pitcher. He also led the AA with 274 walks (and his 4.8 walks per nine innings was third in the league). He finished the year with a 27-34 record and a 3.61 ERA.

Baldwin kept his options open after the 1889 season, which wound up being his only season in the AA.

That November, he met with the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players (a very early form of the MLBPA), where plans were being formed to create the revolting Players’ League. On the 21st, he officially signed with the Chicago chapter of the PL, which would ironically be named the Pirates.

Four days later, Baldwin was on a train to St. Louis, acting as representative of the PL to convince other ballplayers to jump ship to the revolting league. Among the players he helped “pirate” away were four players from the St. Louis Browns, owned by Chris von der Ahe, the same man who objected to Baldwin’s appearance in the 1886 World Series.

I’ve written about the Players’ League before, but if this is the first time you are hearing about this, here’s an excerpt from my work on Pittsburgh’s PL chapter that gave a brief, oversimplified history on it:

Frustrated with the reserve clause, as well as salary limits imposed by the league, John Montgomery Ward, then of the NL’s New York Giants, formed the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players, a very early version of the MLBPA in 1885.

A Columbia Law School graduate, Ward was joined by a sizable chunk of the NL’s playing populous at the time, voicing their concerns about the owners’ power over the league.

Despite their objections, things only worsened between the league and the union, and on November 4th, 1889, after the conclusion of the season, the Brotherhood declared their intentions to leave the league and form their own. A month and a half later on December 16th, 1889, they did just that.

Officially known as the Players’ National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs, the league was commonly known as the Players’ League. Ward was very influential in assuring that the idea rose from a threat to an entity.

Baldwin posted a 33-24 record in the PL with Chicago, totaling 492 innings and pitching to a 3.35 ERA. His 249 walks and 206 strikeouts were both league leaders as well.

The PL would collapse after just one year, however. They had the talent and the audience (having stolen many of the in-game attendance numbers away from the NL and AA), but they did not have the money to keep the league going.

After the PL closed operations, most of the players who had jumped ship simply reverted back to their old NL/AA teams (except Lou Bierbauer, infamously). Baldwin went to sign back with Columbus, despite manager Gus Schmelz claiming there was no room in the Solons’ rotation for him.

However, after meeting with J. Palmer O’Neill, president of his hometown club in Pittsburgh, Baldwin signed with the team on March 1st, 1891.

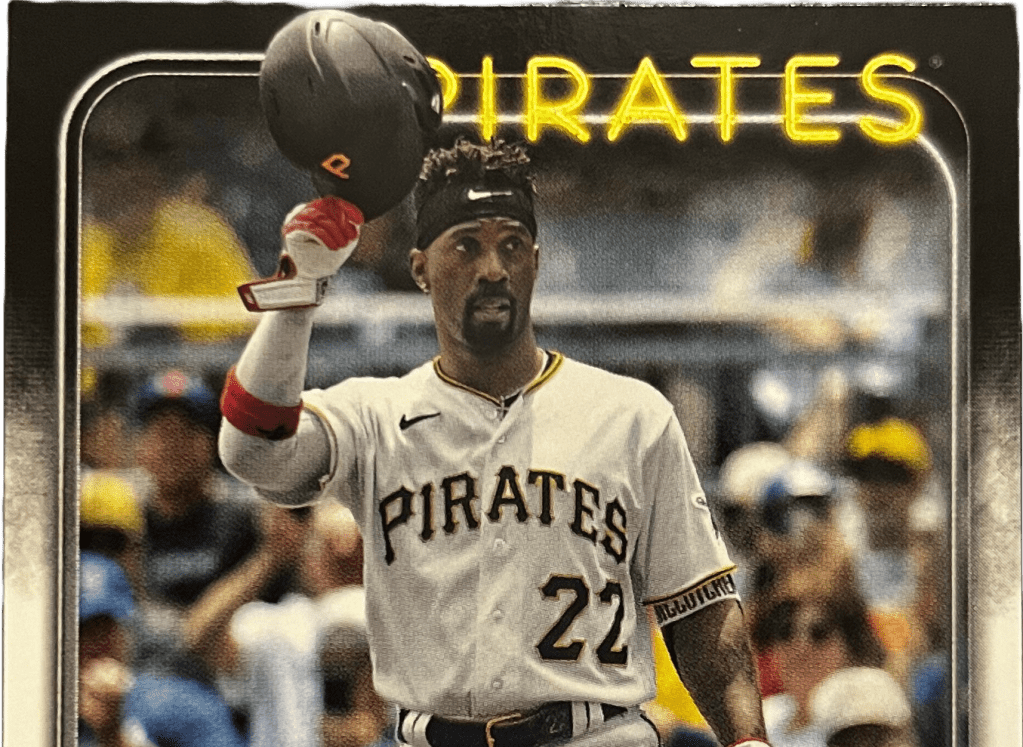

The Pirates, as they were soon to be known, were looking to bounce back from a season that saw their roster pillaged by PL defections, and the remaining scrap of players finish 23-113-2 (.169 winning percentage), which still stands today as the worst record in franchise history.

Two days later, Baldwin went back to St. Louis, once again on a recruiting trip for his new team and once again set his eyes on the Browns.

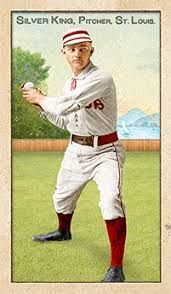

When von der Ahe found out that Baldwin had successfully convinced pitcher Silver King to leave and sign with Pittsburgh, he was furious. The Browns’ owner had not gotten over Baldwin’s efforts from a year ago to raid his club, and after he found out about King’s planned departure, he sought Baldwin’s arrest.

On March 5th, at the Laclede Hotel in St. Louis, Baldwin was in fact arrested on charges of conspiring with O’Neill and Pittsburgh’s manager, Ned Hanlon, to steal King away from St. Louis., who von der Ahe claimed was under contract with the Browns.

“I expected they would put up a job and have me arrested,” Baldwin said of his brief imprisonment. “But the charge will not stick. I never attempted to bribe anybody or conspire with anybody. When I get out I am going to see von der Ahe. I will sue him for false imprisonment, and I will have the Pittsburg League [sic] club behind me.”

The charges were eventually dropped, and Baldwin would in fact sue von der Ahe in Philadelphia, where he sued von der Ahe for malicious prosecution and false imprisonment, seeking $10,000 in damages. The case sat for years, prompting Baldwin to refile it in Allegheny County.

Meanwhile, King was eventually allowed to leave St. Louis and join Baldwin in Pittsburgh. Baldwin’s 2.76 ERA was the team-leader among regularly appearing arms for Pittsburgh. However, he posted a 21-28 record that year and led the NL with 23 plunked batters.

Some early season shoulder soreness led to him bickering with local media, and that contentious relationship lasted during Baldwin’s entire tenure with Pittsburgh. Despite some struggles, he did re-sign with the team.

His teammate, King, the man he quite literally went to prison for, struggled to a 3.11 ERA and led the league with 29 credited losses. The 1891 season was his only year with the Pirates.

The following year, 1892, was quite turbulent for Baldwin. He got the Opening Day start for the Pirates, a 7-5 win over Cincinnati, but he continued to fight with local media and was involved in some off-the-field incidents.

On July 6th of that season, the same day as a 9-8 Pirates loss to Washington, Baldwin was involved in the infamous Homestead strike of 1892, where striking steelworkers from Carnegie Steel and members of the Pinkerton Detective Agency’s private police force, hired on behalf of Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick, violently clashed in the city.

For his part, Baldwin allegedly helped incite a riot and passed out rifles to striking steelworkers. The strike is considered one of the most violent labor disputes in US history and a definitive loss for striking workers and their unionization efforts.

Six days after the incident, on the 12th, Baldwin reportedly met with the president of the Brooklyn club in the NL and asked for the team to acquire him via trade. Baldwin went far enough as to suggest that Brooklyn send back pitcher Tom Lovett back in the deal. Pittsburgh was reportedly willing to make that trade, but Brooklyn was not.

Shortly after that, on August 5th, the Pirates grew tired of his poor play and decided to give Baldwin a ten-day break, without pay, as a result. They then gave him a ten-day notice of releasing him. Media speculated that this would be welcome news to Baldwin, who they described as unpopular among patrons of the Pirates.

The decision by the club to release him when they did may have been sped up after Baldwin’s father had harsh words for the club after a game the day prior. It has also been speculated, but not confirmed, that Baldwin’s release was in part due to the incident at the Carnegie Steel strike.

A warrant went out for Baldwin’s arrest in September for his connections to the strike, charging him with aggravated riot. Lawyers for the company had reportedly been watching Baldwin ever since that July morning, and claimed to have found people willing to testify that Baldwin was in the crowd on the 6th and participated in the violence.

Baldwin maintained his innocence, but turned himself in shortly after, accompanied by his father, who paid the $2,000 bail to free Baldwin.

On September 23rd, Baldwin was once again arrested, along with well over 100 other defendants, on the same charge, but was never brought to trial.

His 1892 season ended with Baldwin posting a 26-27 record and a 3.47 ERA. He led the league for the second straight season, with 22 hit batters. He never could fully master the control of his pitches.

Obviously, he and the Pirates did not come to an agreement on another contract, and Baldwin briefly pursued a career in real estate during the offseason, saying he had no desire to return to baseball.

However, Baldwin would soon reverse course and on February 16th, he re-signed with the Pirates for $2,400, the same salary as the year prior. Baldwin looked shaky in spring training and exhibition action, and during his first start of the 1893 season, he lasted only 2.1 innings and allowed four runs.

He was subsequently released on May 3rd, before making another appearance for the club, an unceremonious end to a rollercoaster of a tenure in Pittsburgh.

He would eventually sign in New York with the Giants, ironically replacing Silver King in their rotation. He recorded a career-high 4.10 ERA and went 16-20 for the Giants, who finished fifth in the NL in 1893; Pittsburgh finished second.

Baldwin was released before the 1894 season and found it hard to find work. Media speculated that his ongoing feud with Browns owner Chris von der Ahe was a reason as to why no big league clubs were willing to take him on. Baldwin was forced to resort to playing in independent and minor leagues for 1894.

Baldwin had refiled the case in Pittsburgh, where it was taken up. On March 3rd, 1894, von der Ahe walked into Pittsburgh’s home of Exposition Park III and was arrested by a deputy sheriff and taken to jail. Pittsburgh’s president then, William Nimick, paid von der Ahe’s $1000 bond.

At a subsequent trial, Baldwin won $2,500 in damages from von der Ahe. In February of 1896, von der Ahe was granted a new trial, on the grounds that an attempt to influence the jury had been made. However, he was no more successful in his second try; Baldwin won $2,525 in January of 1897, which probably came at a good time for the hurler, because Baldwin’s former owner, Albert Spalding, had also sued him in 1897 for the money he loaned Baldwin all those years ago.

Nimick, years after paying von der Ahe’s bond, wanted his money back, but he was unresponsive to requests. To secure a return of his money, Nimick devised a plan to lure von der Ahe back to Pittsburgh and hired a private detective to help hatch the plan.

It involved sending von der Ahe a fake telegram from a “Robert Smith,” who invited von deer Ahe to lunch at the St. Nicholas Hotel. When he arrived, Nimick’s private detective more-or-less kidnapped him and put up on a train to Pittsburgh, where he was taken to court in Allegheny County.

Finally, seven years after Baldwin’s original lawsuit, von der Ahe paid him $3,000.

Baldwin bounced around various leagues for the next two seasons. He briefly signed contracts with two major league teams, but was released before getting a chance to suit up for them.

His final recorded stats came in 1895 with the Pottsville Colts in the Pennsylvania State League, where he went 4-3 with a 3.95 ERA.

After baseball, Baldwin started medical school in the fall of 1898, graduating two years later and practicing medicine in multiple cities, including at the Passavant Hospital in Pittsburgh, during his later years. He never married.

Baldwin died at that very hospital on November 10th, 1929, at the age of 66, after a long battle with illness. But his legacy within baseball and in Pittsburgh lives on. His “piratical” story often gets lost in the many illustrious names that have suited up for this organization, but the next time someone asks you how the Pirates got their name…you’ll have two stories to tell them.

(A huge thanks to the Society of American Baseball Research for this project. This article by Brian McKenna provided a great amount of background knowledge on Baldwin’s life and baseball career)

Leave a comment