When one does a simple Google search for “first night baseball game in Pittsburgh” they’ll find results for a game from June 4th, 1940.

It’s a result that details a game between the Pittsburgh Pirates and Boston Bees (present day Atlanta Braves), where on an early summer night, the Pirates played their first night game at Forbes Field in the Oakland neighborhood.

A crowd of 20,310 watched the hometown team blow out the Bees 14-2, with every Pirate batter getting on base, all but one scoring at least one run, and all but one notching at least one hit. Second baseman Frankie Gustine led the way with three hits, and first baseman Elbie Fletcher drew an impressive four walks.

On the mound, Pirates righty Joe Bowman tossed one of his ten complete games that night, holding Boston to just five hits and two walks, striking out three.

The game was a massive success on and off the field, with the Pirates recording their highest attendance of the season to that point.

And while yes, this game was very important to baseball’s story, both in Pittsburgh and nationally, its place in history is technical. This was not the first night baseball game at Forbes Field. It was the first one that counted.

The honor of playing the actual first night game in the area belongs to the Homestead Grays, who made the foray into nocturnal baseball ten years prior.

Back in 1930, the Grays made history when they met up with the Kansas City Monarchs in the midst of a barnstorming tour. It was then, during an exhibition game between two powerhouses of Negro League baseball, that the first night baseball game at Forbes Field commenced.

The Monarchs are one of the most storied franchises in the history of Negro League baseball. A member of the Negro National League from 1920 until its collapse in 1931, and later members of the Negro American League from 1937 until 1961, the Monarchs won a total of 12 league titles and two Negro World Series championships.

When the Grays met the Monarchs in 1930, Kansas City was coming off of their fourth league title in seven years. Managed by outfielder Bullet Rogan, he and the Monarch management had assembled quite the roster around him.

They would finish the 1930 season with a decent 40-23 record, good for second place in the NNL. But no one could catch the St. Louis Stars that season, who finished 69-25, a full 13.5 games ahead of the Monarchs.

Despite all of Kansas City’s success on the field, however, the Monarchs were also pivotal in introducing night baseball to the masses.

Seeing it as an opportunity to play more games (and therefore, make more money), Kansas City did a little tour of the United States, meeting up with other Black teams of the time and staging night games wherever they played. They were the first professional baseball team to use and transport a portable lighting system that made night games a reality.

The Monarchs acted like a caravan when they traveled. Five trucks would transport their lighting equipment from city to city, including a “lighting plant” that was built exclusively for the Monarchs’ use. Another five would carry the team and assorted club personnel, and Kansas City club personnel would work diligently to set the stage.

Their night game against the Grays at Forbes Field was actually part of a much longer series of barnstorming games between the two. They started in Cleveland on July 16th of that year, playing in front of a crowd reported to be around 10,000 in size.

The next night, the teams traveled to nearby Akron for another game, before their time in Pittsburgh.

Setting up in Pittsburgh was no small feat, however. Forbes Field famously had one of the larger playing surfaces in baseball, at the request of Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss back in 1909, who oversaw the construction of the park. He hated what he called “cheap” home runs and would have no ballpark built on his dime that offered them.

As such, Forbes Field required a ton of light to properly illuminate the space.

Six lighting towers were placed in the balcony, and six extra lighting projectors were used to help supplement the balcony lights. It was the only ballpark on Kansas City’s tour to use lead lining to support further lighting throughout the park.

In all, 35 projectors, each with three 1,500-watt lamps, helped illuminate the game. By the time it was set up, Pittsburgh’s ballpark reportedly had more light shining on it than any other park the Monarchs had played in during this tour.

Preparations were made in expectation of 15,000 fans heading to the stadium that night, and it did receive a decent amount of media coverage as well.

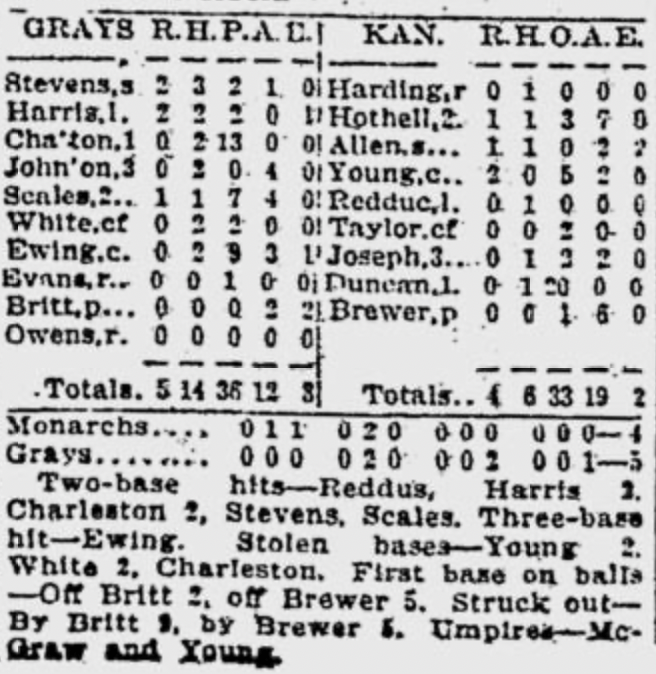

Finally, on July 18th, 1930, the game was set. An 8:30 PM first pitch saw the Grays and Monarchs make history in the Oakland Orchard. Even though it was, in the end, just an exhibition game, it was an impressive win for manager Cumberland Posey’s Grays.

Kansas City got out to an early 4-0 start, although their offense was a little sporadic. The Monarchs scored runs in the second, third, and fourth inning off of right-handed pitcher George Britt.

Some of Britt’s early struggles were self-inflicted; Britt recorded a pair of errors early on, misplaying a fielding chance and later making an errant throw while trying to pick off a runner at third base.

His battery mate also struggled early on. Buck Ewing, the Grays’ catcher, had an error of his own in the third inning, when he failed to corral a pop up that eventually contributed to a Monarchs score.

Britt would settle down later in the game, though, and pitched much better as his teammates provided him with some run support.

Homestead struck back in the fifth, powered by a Vic Harris double. The Grays scored two runs in the fifth, but they could not tack on another run for the next little while.

Britt would hold off the Monarchs through the ninth, giving his Grays one last chance, down two, to rally. And Homestead did just that. Jake Stephens (whose last name is listed as Stevens in the game report), hit a single to start the inning, and went to third base on another double by Harris.

Oscar Charleston, a future Hall of Famer (and eventual manager of the Pittsburgh Crawfords), then lined a double into left field, bringing home both Stephens and Harris, tying the game at 4-4 and giving Homestead a prime chance to win it.

As Judy Johnson struck out, Charleston successfully stole third, and with the Monarchs opting to intentionally walk George Scales (who led the team with a .398 batting average that season), the Grays had runners on the corners with just one out.

But, it was not to be in the ninth. Chaney White, with a chance to win it, instead hit into a double play, which sent the game into extras.

Remarkably, Homestead found themselves in a very similar situation in the bottom of the 11th inning. Stephens led off that half inning with a single, and advanced to second on a fielding error.

Stephens reached third as Harris grounded out. This time, it was Charleston who was intentionally walked. Even though Charleston was swinging a hot bat, the Monarchs were likely playing for the double play again.

Either way, however, Johnson hit into an inning-ending double play, prolonging the game.

Finally, in the 12th inning, the Grays completed the comeback. Scales notched a single and once again benefitted by sloppy defense in center field, allowing him to go to second. White then singled down the first-base line, setting up Ewing with the game in hand.

Ewing, who had that error weighing heavy on him, redeemed himself with an infield blooper and beating out the throw to first to seal the game for his Grays.

From an entertainment perspective, it was pretty much a perfect game.

What was slightly less than perfect were the lighting conditions in this one. Ewing said after the game that he was unable to see a few high pop-ups, which might explain his aforementioned error. Additionally, the large apparatus of lights made fielding for pop flies in foul territory a challenge.

But overall, problems with visibility or playing concerns proved to be minimal, and outfielders had no complaints about the amount of light.

The game, a triumph on its own, was the latest in a series of games played between the Grays and Monarchs. The teams played a second night game at Forbes Field the following night, where Kansas City got their revenge. In that game, the Monarchs scored five runs in the ninth inning, staging a comeback of their own to beat the Grays.

That loss gave Grays’ 44-year-old right-hander Smokey Joe Williams his first loss of the 1930 season, and he future Hall of Fame hurler wouldn’t forget it. Later that year in August, in another meeting between the Grays and Monarchs, where Williams famously struck out 27 batters in a 1-0 win.

From their nightcaps in Pittsburgh, further trips included Sharon, Pennsylvania (about an hour and 15 minutes away from Pittsburgh, by car), Altoona, Scottsdale, Beaver Falls, Youngstown, and then later returning to Forbes Field for a few additional games.

The Forbes Field night games were early participants in the renaissance of night sports in the area. In the fall of 1929, Duquesne University and Geneva College drew 24,000 in a night game, and it was the first of several night contests the Dukes would go on to organize.

At the time, the idea of night baseball was still considered “experimental.” The Monarchs were simply trying out a fun new idea, and although their work with the Grays went (mostly) smoothly and was a success with the fans, there was still concerns over whether the idea could successfully translate to the major leagues and work consistently.

Five years later, Major League Baseball would hold their first official night game at the legendary Crosley Field in Cincinnati. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was in attendance, and flipped the honorary switch that turned the lights on inside the ballpark. A crowd of 20,422 (their sixth largest of the season) watched on as the hometown Reds defeated the visiting Philadelphia Phillies, 2-1.

Over the coming years, night baseball would become more and more common. More and more teams broke the sunlight barrier, with the Chicago Cubs standing as the last holdout. Wrigley Field did not install lights all the way until 1988, and their first-ever night game was rained out.

Today, about two thirds of all MLB games are nighttime matchups.

Pittsburgh would host the first night World Series game, when the Pirates hosted the Baltimore Orioles at the newly-built Three Rivers Stadium in 1971. It was a crucial Game 4 win for the Pirates, evening a series they would eventually claim in seven.

But in talking about the history of nighttime baseball in Pittsburgh, the Homestead Grays will always hold a crucial part of that story.

(I want to give a huge thank you to the Google News Newspaper Archives for all of the historic papers they have documented online. Without it, this story would not have been possible!)

Leave a comment